Someone Famouse Who Went to School to So Art

David Shrigley

Glasgow School of Art BA, 1988-91

I thought my degree show was bright, but the people who were marker information technology didn't. I got a two:2. They didn't appreciate my genius.

There were big photos of things I had fabricated, including Leisure Eye, and some very silly sculptures: a child-sized coffin with a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles relief on information technology, a behemothic hurdle called The Offset Hurdle, and a giant walnut whip that had a little door in it. I don't really know what I meant by that piece. I didn't sell annihilation at the show – information technology was 1991, before the YBAs. There wasn't a precedent for people selling work that wasn't figurative painting.

I was angry and bitter virtually my 2:2. My friend Malcolm got a commencement. He'd made a water feature, which I thought was pretentious and stupid. At the concluding testify, somebody's mum got really drunk and fell into Malcolm's water feature.

Gillian Wearing

Goldsmiths MA, 1987-90

My final works were crates with objects inside – a bicycle seat protruding from 1, pumps coming out of another. I also did a remake of the Duchamp bicycle wheel with a country-of-the-fine art wheel loaned from a bike shop. The Duchamp piece notwithstanding relates to my work – the thought of remakes. I had originally fabricated the crates myself, only for the final evidence I panicked and had them professionally made. It made them anaemic. I was disappointed – I knew they had looked better. Subsequently I destroyed most of the crates, gave back the wheel, threw away the chair, and turned one crate into my bed.

You always hope something will come of your degree bear witness, although I didn't call up it was going to. And nothing did. The one thing I think was that Michael Landy – who wasn't my partner and then – came and said that he really liked the wheel slice.

The twelvemonth above me were very exciting: information technology was Damien Hirst and Michael Landy, and they were all in Freeze. But the first conversation I had when I arrived at art schoolhouse was that when nosotros left we virtually likely wouldn't be artists. I recall saying, if I have one exhibition when I go out I volition exist happy. That's all I expected.

Tracey Emin

Royal College of Art MA, 1987-89

I felt very lost at the RCA. It was very conservative, not-experimental and non-political – the absolute contrary of Maidstone College of Art, where I did my degree. At Maidstone everything had a Marxist slant. The women from Greenham Common came in, the striking miners came in, and a member of Sinn Féin. Real life was brought to us.

I made a few friends at the RCA – Rachel, who ran the shop and gave me tubes of paint, Susan the secretarial assistant, and lovely Stan the caput porter. My best friend was David Dawson, who went on to great things, and was Lucian Freud'south assistant for xx years.

I showed 5 big-calibration oil paintings. They were a cross between Edvard Munch and early Byzantine frescos. I had never used and then much oil paint, or stretched a canvas before, and I learned so much, including what kind of artist I didn't want to be: I didn't want to be a Sunday painter, I wanted to make a difference in the world. I wanted to benefit things through my fine art.

At the RCA, it was incredibly competitive what space you showed in. I was put in the basement, under a mezzanine. I knew I was at the bottom of the pile, and then I didn't bother fighting. Some of my paintings were 7ft by 8ft, and there was a 3cm gap between them and the floor and ceiling, but at least I didn't have to slumber with any of the tutors.

My bank manager Mr Day came all the mode from Kent for the show with his wife. He had more or less financed my way through my MA. Without him and the hardship fund, I doubt I would take made it to the end.

I was terribly scared near my future. I sold some paintings, and made well-nigh £2,500, but nowhere near enough to pay dorsum the bank. Afterward I left, I was homeless, became pregnant and had a total breakdown. Eventually, I got a job working for Southwark council as a youth tutor and did a role-fourth dimension philosophy form. I got my brain back into shape, paid back all my debts and started making art over again.

Gavin Turk

Majestic College of Art MA, 1989-91

I get misrepresented every bit an excuse for art students to do nada during their degrees, and so turn upward and think everyone owes them something. I was really pretty busy at the Regal College. I wanted to make work about retentivity and site, heraldry, tradition, community, culture and death. I was in Due south Kensington, surrounded by all these English Heritage blue plaques, and I thought information technology was the perfect zilch for my message.

Unfortunately, Jocelyn Stevens, rector of the RCA, had just been offered a job as the head of English Heritage, and I think he idea I was making a comment about him. I failed my caste, and it became news – that you lot could make art, and information technology could be judged as non proficient enough.

I felt terrible at the time. I just wanted to be like everybody else. I didn't want to exist singled out. I had plans of going travelling round the earth, and consoled myself by cancelling all my trips.

Only in hindsight, I wouldn't accept wanted it whatsoever other style. Information technology seemed more interesting to talk well-nigh the fact that there was an edge of acceptability. That there was art that could go wrong. It became more positive than if I'd been waved out with a handclapping, clap, handclapping. I've since made three versions of the piece of work. I sold 1 to Charles Saatchi, i to Jay Jopling and 1 to the Tate.

Conrad Shawcross

Ruskin School of Art BA, 1997-99

I made this 7m tower out of pine forest. It was a pseudoscientific instrument from which I could append myself and play a single note that would be my ain weight. It was a metaphysical idea near the soul and individuality.

I got a first. I've been lucky, I've always felt driven and full of ideas. Early on information technology was going to be fine art or architecture – there's a photograph of me at six years old with a tower I built in my bedroom. I was trying to build something as tall every bit possible and it was very precarious. At the fourth dimension my mum thought information technology was quite impressive.

In the end, I didn't have the patience to be an architect. All the rules and regulations would take been frustrating. The good thing well-nigh fine art is that you can do what you like – fifty-fifty if it's actually pie in the heaven. Gravity is my biggest obstacle.

Conrad Shawcross: Inverted Spires and Descendent Folds is at Victoria Miro Gallery 2, London, x June–31 July 2015

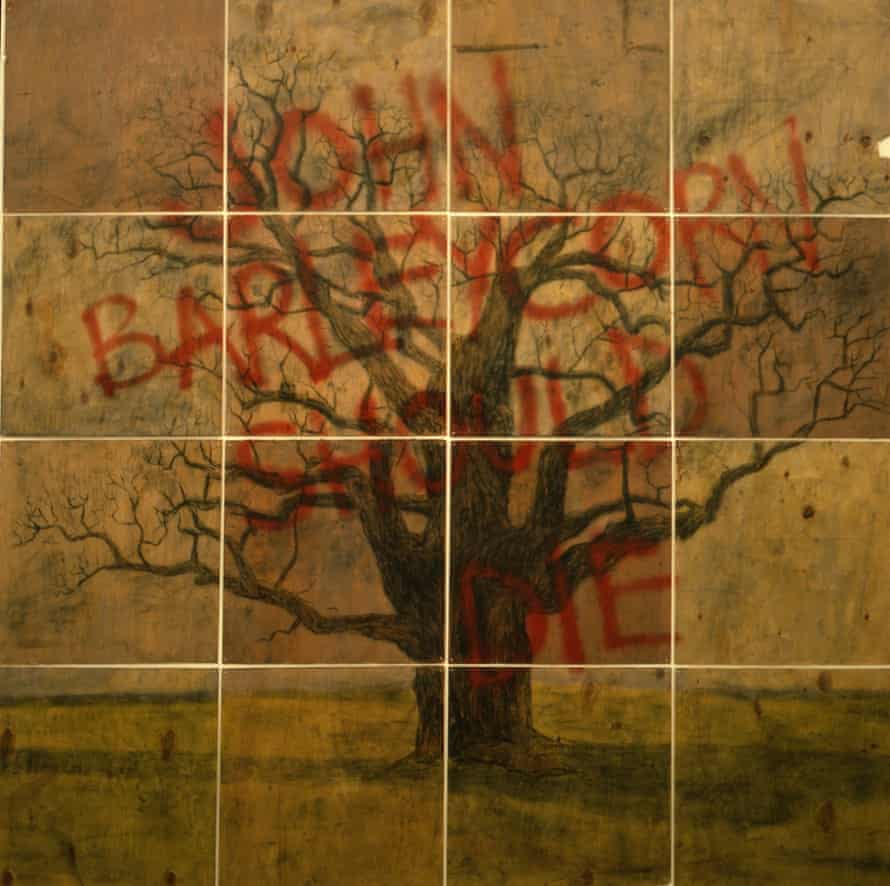

Mark Wallinger

Goldsmiths MA, 1983-85

I had the run of a huge space at Goldsmiths that summertime, so it was a very productive time. I showed iv large pieces called National Trust, Stately Home, Hearts of Oak, and Where At that place's Muck. This was post-Falklands war, it was the miner's strike, the showtime of privatisation. I'd been reading EP Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class. I was juxtaposing my lived reality with a Conservative political party broadcast which was rolling hills and Elgar. I was probably rather aroused at the time.

Back in the 80s, in that location was no fine art globe to speak of. Nothing sold dorsum and then. I worked role-time in a bookshop, then I got teaching work. You did what y'all could to sustain yourself. We had a course entitled Life After Art School and i of the pieces of communication was never go a job that interests you lot too much, the idea being that then you will still make art.

Where At that place's Muck is now hanging in Tate United kingdom. It's quite odd to see it at that place. Information technology's a funny affair getting older – I yet recollect making it to the last particular. There is a concrete memory of making information technology, which is very immediate.

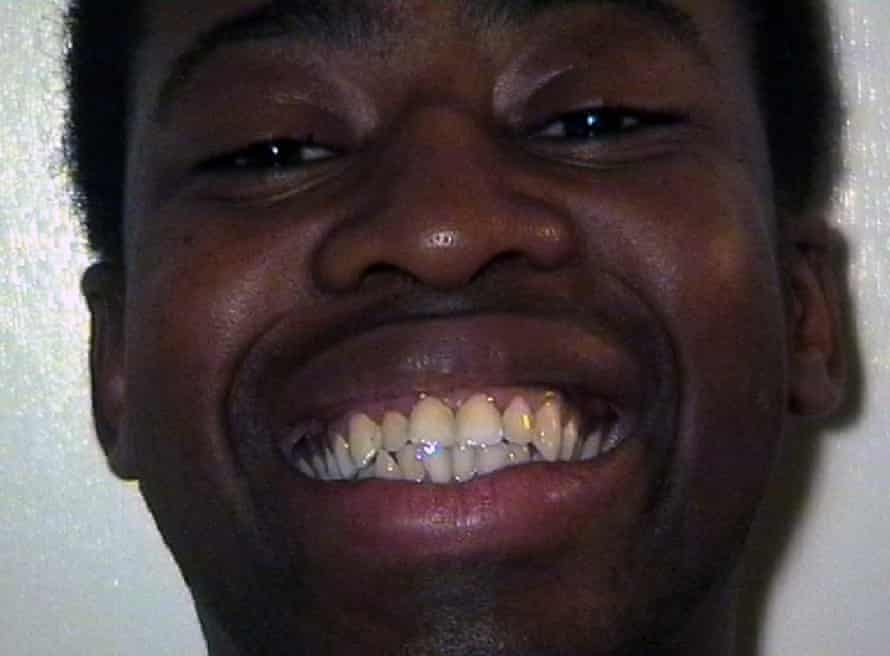

Harold Offeh

Royal Higher of Art MA, 1999-2001

The status of the Royal College show ways you get thousands of visitors. I was the post-YBA generation, and it was fabricated very clear to usa that there were dealers there. While we were still setting upward, Charles Saatchi was stalking around, rifling through people's half-hung work. He wanted to see the shows before they were installed.

This still is from my picture Smile, which was me smiling for 34 minutes to the song Smile, written by Charlie Chaplin. I was interested in our responses to pop songs. For me, art wasn't a commercial thing, just at the terminal prove there was a scrap of bitchiness about whose piece of work was selling. It was, "Ooh, look – she's got three red stickers. How has that sold?"

Nicole Wermers

Central St Martins MA, 1999

I did a series chosen Vacant Shops, based on closed down buildings I'd seen on Oxford Street – often obscured by paint or posters – a mix of emptiness and anarchy. The models came upwards to your belly button, and then you could lean over and see the whole space.

I still love them. They were the starting time proper piece of work I made and I am yet interested in the aforementioned ideas: the cribbing of public space, how places tin can be subverted. In the shops, the display compages has fallen downward and revealed itself to be fabricated of inexpensive cardboard.

For the last iii months of the St Martins MA, students were given these super lovely, big studios in Soho. I had a actually big 1 on the eighth floor, overlooking the rooftops, and I adored it. I was there every 24-hour interval and every night. It was correct in the middle of the urban center, and then I could sneak out for a coffee and run around in the city for a while, then go back to the studio.

Unless you become very rich, it'south impossible to live like that after. It was a very brief moment when I had the run a risk.

Asif Kapadia

Royal College of Art MA, 1995-97

I wanted to written report film at an art school – I loved the thought of being surrounded by designers and artists. We were encouraged to exist experimental. I fabricated several short films with very lilliputian dialogue. I'thou still not a fan of talking heads. My stories are told with images equally much as possible. My final short pic was very ambitious – we went to Rajasthan to make a fairytale.

The final show was amazing. Everybody who is everyone in the industry was in that location. Martin Scorsese was being given an honorary doctorate, and ane of the tutors asked if at that place was a student pic he especially liked. He mentioned our motion-picture show. There was a dinner after the last show just for the tutors, but I was smuggled in to meet Scorsese over dessert.

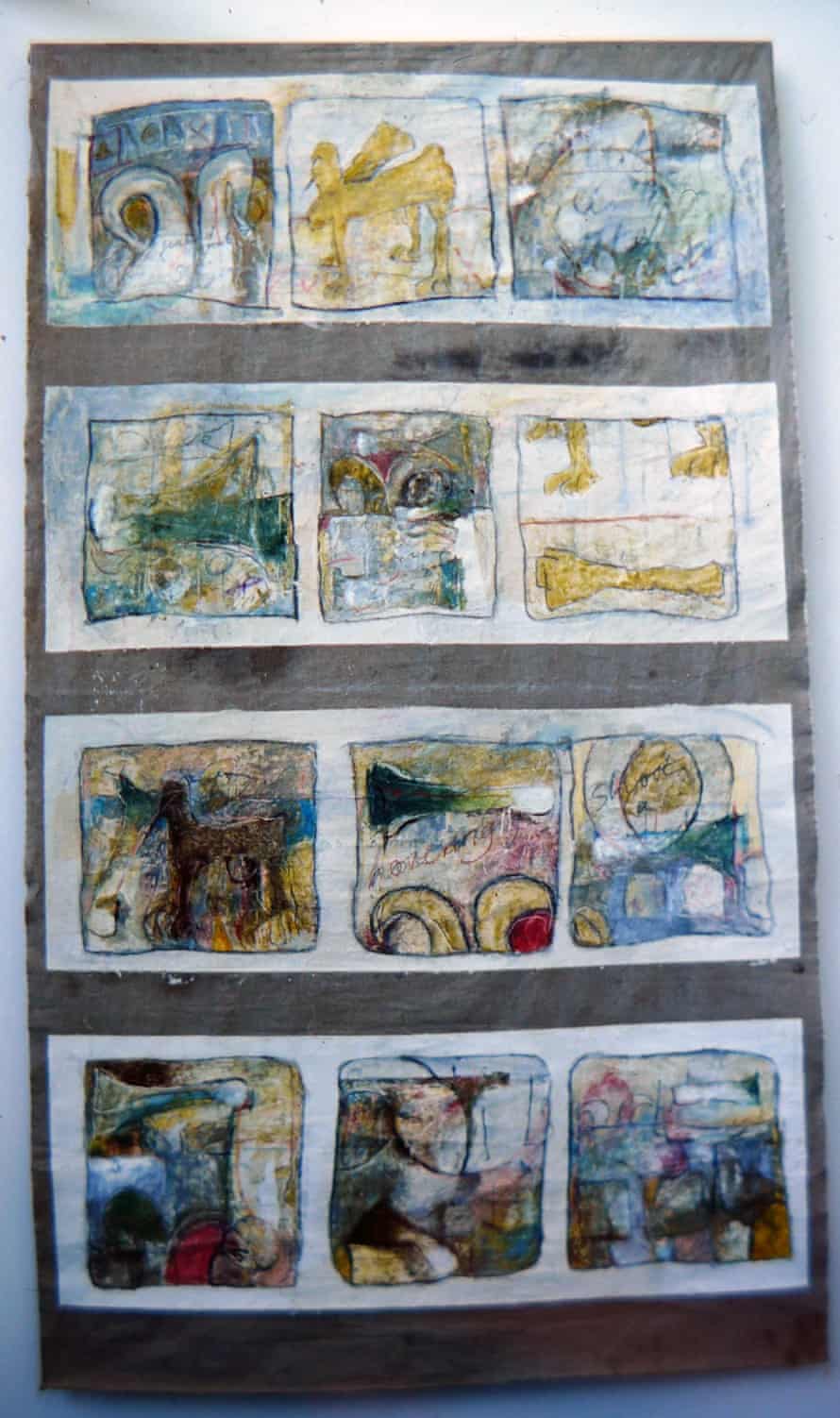

Tacita Dean

Falmouth Art Schoolhouse BA, 1985-88

I got a start. I was the only one, then information technology was pretty amazing. I'd e'er wanted to be an artist, ever since I was a child, and I was a driven student. I knew what I was doing, I was clear-sighted and I wasn't afraid.

I was on the painting grade, merely I was never really able to make a painting. I worked with trashy materials – layout pads, which I'd cover in rabbit-skin mucilage and gesso. I was developing my ain mythology inspired past the Delphic oracle and the Sphinx.

The prospect of selling any piece of work back and then was a fiction. Information technology was a completely different universe. I retrieve one of my lecturers bought a drawing for £five, and a vagrant man bought a lactating sphinx with huge breasts for £ten. I never saw the coin.

You never imagined you would take a career in art – or, if you did, your career would be living in a garret in Paris drinking absinthe. When I talk to students now they are thinking about what gallery they should get earlier they've made any work. That need for validation by the market is and so destructive.

I'g glad I was a student in the analogue era. Nosotros had no television, no phones; in that location was one telephone box that we had to queue upwardly for. It was freeing to have no hope. I studied from 1985 to 88. Damien Hirst was 86-89. It was the generation that were nearly to change everything.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/23/before-they-were-famous-art-stars-final-degree-shows-tracey-emin-david-shrigley

0 Response to "Someone Famouse Who Went to School to So Art"

Post a Comment